An Ultimate Guide to Ontology for Your PhD Thesis

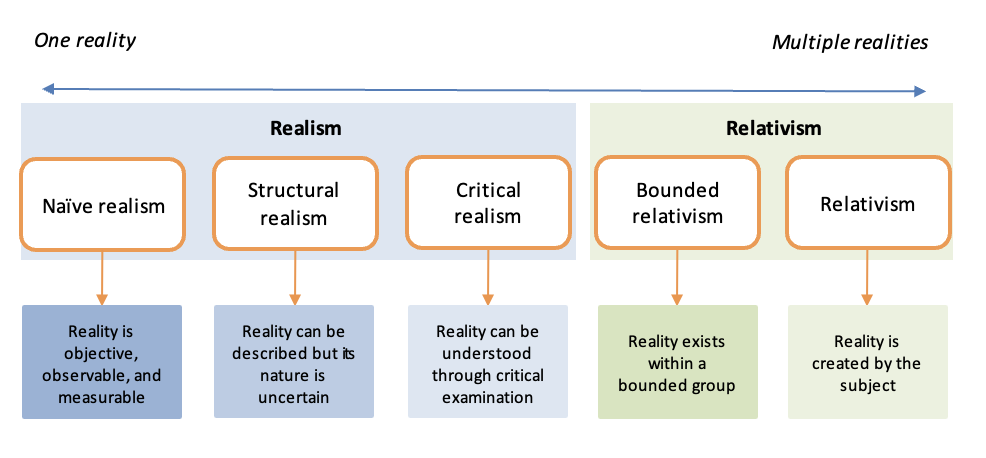

Understanding philosophy is a cornerstone of social science research because it underpins theoretical thinking and provides clarity about the decisions the researcher makes to obtain and interpret knowledge of reality. Ontology is a branch of philosophy that is concerned with what exists and what is the nature of objects. In its nutshell, ontology is concerned with whether there is one reality that exists independently from the context or there are multiple realities that are shaped and formed by the contexts in which they exist. Based on this description, it is relevant to think of ontology as a spectrum of several ontological positions. For this guide, let’s assume that you are doing a PhD thesis focused on examining the role of leadership in employee motivation to understand how different ontologies could benefit your study.

Naïve Realism

At one end of the ontological spectrum is naïve realism, a philosophical stance, according to which there is only one reality that does not change or is affected by the context in which it exists. Naïve realism can be viewed as the researcher’s belief that their perception of reality reflects it exactly as it is, while the role of previous experiences, emotions, and cultural identities is neglectable. This assumption makes it possible to examine and understand the world objectively using appropriate methods of data collection and analysis. Naïve realism rejects the idea that we should rely on our point of view or anyone’s perceptions and attitudes because they distort and bias reality and can lead to polarisation. A researcher who adopts this ontological stance believes that the concepts of leadership and employee motivation are universally applied. They could be properly described by certain theories and measured by certain instruments. While acknowledging that a world of material objects exists independently of being perceived, the naïve realist overlooks conflicting perceptions, making them miss out on an opportunity to get a deeper understanding of the social phenomenon being under study.

Structural Realism

Structural realism or neorealism is another ontological position in which only one objective reality exists. However, unlike naïve realists, structural realists believe that while scientific theories describe the form and structure of reality, they cannot provide any explanation of its underlying nature. As a result, this ontological perspective posits that the natures of things are either unknowable for some reason or completely eliminated. That is why neorealism is often viewed as a metaphysical modification of scientific realism. When examining the role of leadership in employee motivation, a structural realist would assume that both organisational leaders and their followers are rational actors and their actions could be described, explained, and predicted by certain leadership and motivation theories. At the same, the motives, assumptions, values, and perceptions of these individuals are taken as given or excluded from the study altogether.

Critical Realism

All branches of realism share one thing in common – they assume there is only one reality. Still, the key difference between critical realism and the aforementioned paradigms is that the researcher’s ability to comprehend this reality is limited. To overcome this limitation and understand the layered, complex, and contingent reality, critical realists critically approach facts, events, and partial regularities. Hence, the external world and the processes that occur in this world can be understood only through critical examination. The philosophy of critical realism implies that reality is not entirely constructed through the researcher’s knowledge because it consists of subjective interpretations formed by the conceptual frameworks in which they operate. A critical realist would seek to assess the underlying causal relationships between leadership and employee motivation using factual and empirical data to better understand the underlying social issues and provide strategic recommendations as to how to address these issues.

Bounded Relativism

Unlike realism, relativism is based on the philosophy that multiple realities exist. From the standpoint of relativism, the reality is socially constructed within the human mind, meaning each individual has their own truth, which is shaped and formed by their experiences, perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes. One of the forms of relativism is bounded relativism, which postulates that mental constructions of reality reflect themselves as equal within boundaries, regardless of the time and space in which they exist. In other words, according to this ontological philosophy, reality exists within a bounded group, all members of which share this reality and have similar values, knowledge, and perceptions that shape and form this reality. In turn, different realities exist across groups, suggesting that each group has its unique reality that is unlikely to exist in any other context. A bounded relativist would recognise the existence of organisational culture and its potential effect on the relationship between leadership and employee motivation. They would also acknowledge the link between this relationship and the context in which it exists.

Relativism

The ultimate form of relativism assumes that there is no such thing as objective reality. Instead, realities are multiple and they exist as intangible mental constructions. From this standpoint, we all live in a multiverse because it is the subject that forms reality and no reality exists beyond subjects. The way individuals experience the world at any given time and place creates their realities. When approaching the relationship between leadership and employee motivation from the viewpoint of relativism, a researcher would assume that each organisational leader and employee have their understandings and perceptions of what constitutes leadership and how it affects employee motivation. As a result, the researcher would likely follow constructivist and interpretivist research approaches to comprehend these differences and get a deeper insight into the studied relationship.

It is impossible to meaningfully interpret social science research without comprehending philosophy. As this guide has demonstrated, multiple ontological positions exist that enable researchers to recognise how certain they are about the existence and nature of objects and phenomena they are investigating. Ontological philosophies range from naïve realism to relativism, depending on how the researcher views the world around them, what assumptions they make about the legitimacy of what is real, and how they deal with conflicting ideas of reality.

Recommended readings:

Howell, K. (2012). An introduction to the philosophy of methodology. SAGE.

Lather, P. (2013). Methodology-21: What do we do in the afterward?. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 634-645. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788753

Lather, P., & Pierre, E. (2013). Introduction: Post-qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 629-633. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788752

Moon, K., & Blackman, D. (2014). A Guide to Understanding Social Science Research for Natural Scientists. Conservation Biology, 28(1), 1167-1177. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12326

Novikov, A., & Novikov, D. (2013). Research methodology: From philosophy of science to research design. CRC Press.

St. Pierre, E. (2013). The posts continue: becoming. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 646-657. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788754