PhD Proposal: Trust in the Algorithmic Boss: How Do Knowledge Workers in US Tech Firms Respond to AI-Driven Management Tools?

Abstract

This proposal outlines a research project exploring the views of knowledge industry workers on AI-driven management tools. These instruments are widely utilised today for the purposes of monitoring staff performance, providing feedback, allocating tasks, and automating other HRM tasks. With that being said, there exists a gap in knowledge related to employees’ perceptions of such AI-driven management. Some existing studies suggest that these views can be negative due to the low trust in automated systems missing human judgment. Hence, the proposed project utilises a qualitative methodology to identify the cognitive and emotional elements in employee perceptions in relation to AI-driven management. Interviews with 20 participants, including both workers and managers of US technology firms, will allow practitioners to appraise the effectiveness of such HRM strategies and reveal the areas in which they can be improved.

1. Introduction and Problem Statement

Modern human resource management (HRM) in general and the technology sector in particular are generally characterised by the increasing adoption of innovation, including the use of artificial intelligence (AI) solutions. According to Al-Amoudi (2022) and Fui-Hoon et al. (2023), they offer such advantages as automated performance analytics, feedback provision, workflow optimisation, and algorithmic task distribution and scheduling. From a managerial standpoint, this offers substantial HRM efficiency, allowing practitioners to focus on more strategic tasks (Arslan et al., 2022).

With that being said, the negative experiences of such firms as Amazon demonstrate that data-driven management can lead to different forms of bias in appraisals. Moreover, AI systems frequently act as a ‘black box’ where both regular users and industry experts do not fully understand the principles of their functioning (Basu et al., 2023). These concerns are reflected in multiple recent legislative acts throughout the world, including the European Union (EU) Artificial Intelligence Act. However, similar uniform frameworks are presently absent in the US context, which implies that local practitioners may not be limited in their experimentation with potentially problematic practices in this sphere.

2. Proposed Aim and Objectives

The proposed study aims to develop a nuanced and empirically grounded understanding of how knowledge workers in US tech firms perceive AI-driven management tools and formulate their behavioural responses to them. This aim will be achieved via the following research objectives:

- To explore the interpretations of AI-driven management tools by US tech firm employees in relation to their perceived fairness, reliability, and trustworthiness.

- To identify the key factors facilitating or hindering the development of trust towards algorithmic HRM systems (e.g., perceived accuracy, transparency, and consistency).

- To analyse the range of adaptive and resistive behaviours knowledge workers adhere to in response to adverse experiences with AI-driven management tools.

- To formulate recommendations to tech firm managers on how human-algorithm interactions can be improved to achieve superior organisational outcomes for all involved stakeholders.

3. Proposed Research Questions

The main research question of the proposed study is,

How Do Knowledge Workers in US Tech Firms Respond to AI-Driven Management Tools?

It is further explored via the following research sub-questions:

- How do knowledge workers in tech firms appraise the fairness, accuracy, and legitimacy of AI-driven management tools in comparison with human managers?

- What processes are involved in the development of trust towards algorithmic HRM instruments on an individual level, and what system features can facilitate or hinder this process?

- What behavioural strategies are employed by tech firm employees in response to failures of AI-driven management tools, decreasing the quality of their work experience?

4. Literature Review

The proposed study explores the intersection of several concepts and scholarly domains. First, the concept of algorithmic management (AM) emerged in recent years in the works of such authors as Arslan et al. (2022), Budhwar et al. (2022), and Golgeci et al. (2025). According to the definition of the International Labour Organisation (ILO, 2026), it includes all systems using tracked data and similar information to monitor, evaluate, assign, and organise work. In this aspect, algorithmic management includes both advanced AI-driven management tools and simpler and older systems based on workplace rules. The key advantages of AM from the organisational perspective include greater operational effectiveness and lower workloads on HRM specialists. At the same time, studies such as Cebulla et al. (2023) and Wamba et al. (2022) suggest that algorithmic management may also be beneficial for employees by offering an unbiased, fair, and objective system of measuring and appraising their performance. Such solutions can potentially reduce communications between workers and managers and ensure anonymised evaluation and feedback, which may be viewed as a preferable option by many specialists.

With that being said, recent studies in the field suggest the existence of tension related to trust in AI-driven tools (Fui-Hoon et al., 2023; Golgeci et al., 2025). On the one hand, such regulatory acts as the aforementioned EU AI Act introduce the concepts of algorithmic trustworthiness based on accountability, fairness, explainability, and reliability. This draws practitioners’ attention to the problems encountered where employees perceive such instruments as inherently biased or lacking internal consistency (Glikson & Wooley, 2020). With many AI tools being seen as ‘black boxes’, the inability to understand their inner mechanisms raises concerns regarding their capability to deliver fair, legitimate, and accurate performance appraisals in real organisations. On the other hand, the information related to the development of trust towards algorithmic HRM systems remains limited (Shin et al., 2025). While these tools are attracting the attention of many organisations, it is not fully clear what factors can facilitate or hinder their implementation. This study seeks to address this gap in knowledge and help practitioners understand these barriers and supporting elements. It also analyses the range of adaptive and resistive behaviours emerging in response to adverse experiences with AI-driven management tools.

The selection of tech firms from the US context and knowledge workers was substantiated by a number of factors. First, this country does not presently have strict regulations related to AI-driven management tools such as the EU AI Act (Shin et al., 2025). This implies that local employees may be more concerned about these systems that can be implemented by employers with minimum regulatory constraints or supervision, as shown by the cases of Amazon and other major corporations (Heyder et al., 2023). Second, the US has some of the highest levels of technology development in the world, which implies that US tech firms may be the first adopters of the most advanced instruments in this sphere (Kushwaha et al., 2023). This makes the results of the proposed study highly valuable to practitioners due to their potential generalisability to other contexts in the following years. Third, tech firms from developed countries represent the pioneering force of HRM practices’ digitalisation (Mahmud et al., 2022). AI is presently having a direct impact on knowledge workers such as data scientists, product managers, and software engineers. Hence, these audiences may be most aware of its capabilities while also being concerned about the consequences of its adoption. As a result, the analysis of behavioural responses to AI-driven management tools involving tech firm workers may provide unique and interesting insights that cannot be obtained from the members of less digitalised industries.

5. Methodology

The proposed study adopts a social constructivist paradigm, implying that reality is constructed via human experiences and interactions (Onwuegbuzie & Johnson, 2021). This choice was substantiated by the nature of such analysed phenomena as trust and fairness that usually emerge in the course of communication, collaboration, and team dynamics. The study’s focus also informed the use of the qualitative exploratory design and semi-structured interviews as the main method of data collection. These choices allow the researcher to investigate subjective perceptions and lived experiences of the respondents to collect personal narratives and rich descriptions of the studied phenomena (Walliman, 2018). The projected sample size amounted to 20 knowledge workers from US tech firms. They will include such specialists as data scientists, product managers, UI/UX designers, and software engineers using AI-driven management instruments (e.g., productivity trackers like ActivTrak, Jira and Asana project management solutions, automated code review bots, etc.). These knowledge workers will be recruited via the author’s own network of contacts in this industry and via professional networks such as LinkedIn. The researcher will prioritise medium and large companies as primary adopters of AI-driven management instruments.

The results will be analysed using reflexive thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2022). It involves six main phases, namely familiarisation with qualitative data transcripts, initial codes generation, search for key themes, themes’ review, themes’ definition and naming, and final report production. Coding will be performed using NVivo software. The analysis will be iterative in accordance with the suggestions of Mukherjee (2019). Multiple revisions of data, emerging codes, and themes will ensure the integrity, consistency, and comprehensiveness of the resulting list of themes. With that being said, the studied topics can be seen as potentially sensitive, since they involve explicit discussions of problematic experiences with AI-driven management tools. From an ethical standpoint, this implies the need to ensure anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents. All interview transcripts and accompanying notes will not include any personal information, allowing any third parties to identify the interviewees (Bryman & Bell, 2019). Additionally, the selection of medium and large companies for the analysis further minimises the risk of adverse consequences and compromised identity issues even in the case of any accidental disclosures. All collected data will be stored on a personal password-protected device owned by the researcher and will not be transferred to any third parties for any reason whatsoever.

6. Significance and Expected Contributions

From a theoretical standpoint, the proposed study will expand the understanding of trust formation mechanisms in contemporary tech organisations. The body of literature on AI-driven management tools is highly limited at the moment. Hence, this understanding will enrich organisational trust theories with the analysis of non-human agents and their role in trust formation in the workplace. At the same time, the practical contribution of this study will be beneficial to tech leaders, HR professionals, policymakers, and management system designers. By demonstrating how AI-driven solutions affect employee trust and behavioural responses, it will provide actionable insights on how these solutions can be improved to decrease resistance, negative perceptions, and other hindrances and adverse outcomes. Such knowledge can also be valuable for ensuring proactive compliance with future regulations similar to the EU AI Act that can be introduced in the US in the following several years.

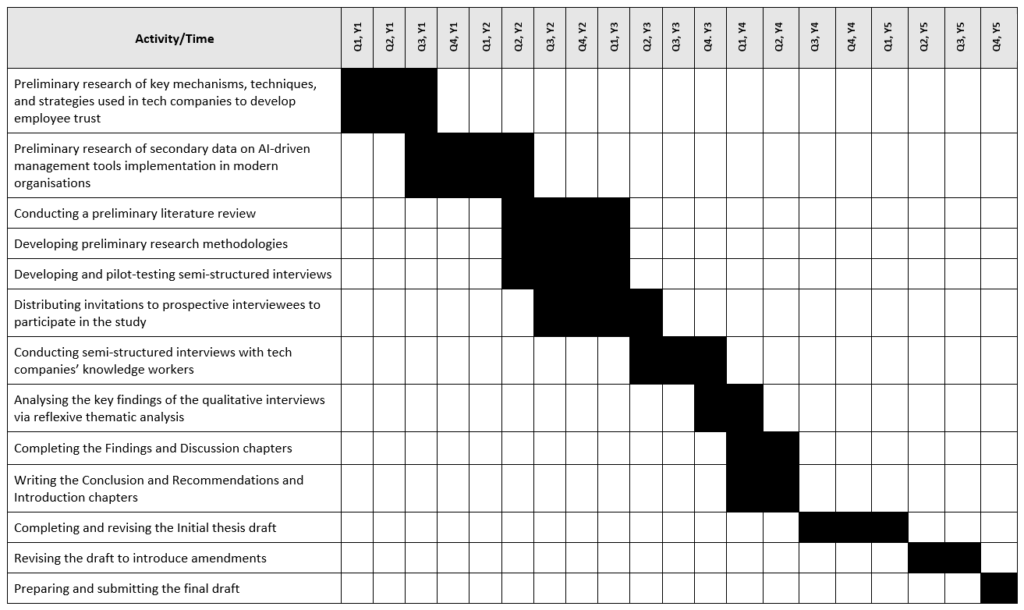

7. Proposed Timeline

The Gantt chart presented in Appendix A outlines the proposed timeline of the study. It implies a five-year plan, where the first year is primarily focused on preliminary research of literature on trust mechanisms and AI-driven management tools adoption in tech organisations. The second and third years are mainly devoted to the development of the Literature Review and Methodology, as well as developing and pilot-testing the qualitative interviews. Years three and four are focused on primary data collection, the completion of the Findings and Discussion, Conclusion and Recommendations, and Introduction chapters and preparing the draft for submission. Finally, the fifth year includes thesis defence and potential revisions.

8. Possible Limitations

The focus on a single sector and a single country can limit the generalisability of the findings to other cultural contexts and industries (Bryman & Bell, 2019). Additionally, interviews represent self-reported data that can also be affected by self-selection bias. In this scenario, employees with stronger negative perceptions towards AI-driven management can demonstrate greater willingness to volunteer. These risks are explicitly acknowledged and mitigated on a methodological level by seeking a diverse sample of respondents.

References

Al-Amoudi, I. (2022). Are post-human technologies dehumanizing? Human enhancement and artificial intelligence in contemporary societies. Journal of Critical Realism, 21(5), 516-538. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2022.2134618

Arslan, A., Cooper, C., Khan, Z., Golgeci, I., & Ali, I. (2022). Artificial intelligence and human workers interaction at team level: A conceptual assessment of the challenges and potential HRM strategies. International Journal of Manpower, 43(1), 75-88. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijm-01-2021-0052

Basu, S., Majumdar, B., Mukherjee, K., Munjal, S., & Palaksha, C. (2023). Artificial intelligence–HRM interactions and outcomes: A systematic review and causal configurational explanation. Human Resource Management Review, 33(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100893

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3-26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2019). Business Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Budhwar, P., Malik, A., De Silva, M. T., & Thevisuthan, P. (2022). Artificial intelligence–challenges and opportunities for international HRM: A review and research agenda. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(6), 1065-1097. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.2035161

Cebulla, A., Szpak, Z., Howell, C., Knight, G., & Hussain, S. (2023). Applying ethics to AI in the workplace: the design of a scorecard for Australian workplace health and safety. AI & society, 38(2), 919-935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01460-9

Fui-Hoon, F., Zheng, R., Cai, J., Siau, K., & Chen, L. (2023). Generative AI and ChatGPT: Applications, challenges, and AI-human collaboration. Journal of Information Technology Case and Application Research, 25(3), 277-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228053.2023.2233814

Glikson, E., & Woolley, A. W. (2020). Human trust in artificial intelligence: Review of empirical research. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 627-660. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2018.0057

Golgeci, I., Ritala, P., Arslan, A., McKenna, B., & Ali, I. (2025). Confronting and alleviating AI resistance in the workplace: An integrative review and a process framework. Human Resource Management Review, 35(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2024.101075

Heyder, T., Passlack, N., & Posegga, O. (2023). Ethical management of human-AI interaction: Theory development review. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 32(3), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2023.101772

ILO. (2026, February 2). Algorithmic Management in the Workplace. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/algorithmic-management-workplace

Kushwaha, A., Pharswan, R., Kumar, P., & Kar, A. (2023). How do users feel when they use artificial intelligence for decision making? A framework for assessing users’ perception. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(3), 1241-1260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-022-10293-2

Mahmud, H., Islam, A., Ahmed, S., & Smolander, K. (2022). What influences algorithmic decision-making? A systematic literature review on algorithm aversion. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121390

Mukherjee, S. (2019). A guide to research methodology: An overview of research problems, tasks and methods. London: CRC Press.

Onwuegbuzie, A., & Johnson, B. (2021). The Routledge Reviewer’s Guide to Mixed Methods Analysis. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Shin, H., Choi, S., & Kim, H. (2025). Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Human Resource Management (HRM): A driver of organizational dehumanization and negative employee reactions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 131(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2025.104230

Walliman, N. (2018). Research Methods: The Basics. London: Routledge.

Wamba, S., Queiroz, M., Guthrie, C., & Braganza, A. (2022). Industry experiences of artificial intelligence (AI): Benefits and challenges in operations and supply chain management. Production Planning & Control, 33(16), 1493-1497. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2021.1882695

Appendix A

Intended Timetable

Appendix B

Interview Questions

I. Interpretations of AI-Driven Management Tools

1. What performance measurement and evaluation tools are presently used by your company? What metrics or feedback mechanisms are used?

2. Tell me about the AI or data-driven tools used in your company (e.g., productivity trackers, automated project management instruments, performance dashboards). How would you appraise their accuracy, convenience, and fairness?

3. Can you recall a specific instance where your experiences with such tools could be described as negative in terms of their accuracy, consistency, fairness or other characteristics?

II. Key Facilitators and Hindrances to AI-Driven Tools Adoption

4. When an AI-driven system provides some appraisal or recommendation, what determines your trust towards its suggestions? What qualities could increase this trust (e.g., greater transparency, more explicit explanations of its decision-making process, etc.)?

5. What level of personal understanding of the system’s internal mechanisms would you deem sufficient for trusting its decisions in relation to your performance appraisals and other HRM procedures?

6. What elements in or personal experiences related to an AI-driven management tool will decrease your trust in it (e.g., biased appraisals, lack of alternative recourse options, wrong results, lack of consistency, etc.).

III. Adaptive and Resistive Behaviours

7. When you were first introduced to AI-driven management instruments, what was your initial reaction to them?

8. Have the discussed tools changed the way you work? Have you noticed any situations where the introduced metrics forced you to work towards them even when this seemed counter-productive? How did you respond to such potential problems?

9. Do you presently have sufficient autonomy to not feel constrained by AI-driven management tools?

10. If you strongly disagree with the assessment or directive from such instruments, what recourse options do you have? Have you tried using any of them so far?